Faith in Diversity Newsletter - 4.24.25 - Spring Refusals

Spring has sprung in the temperate regions and northern hemisphere, and with it, a host of lively seasonal observances. The dark of winter has passed, and some of the cold too (in Florida, firmly, though I understand it snowed this week in Albuquerque, New Mexico.) Spring is a time for flowers (and allergy induced sneezing courtesy of pollen storms). Spring is a time for new life. Some religious and cultural festivities celebrate this blooming.

But some major religious observances defy a purely sunny look on the season. Easter, Passover, and the Sikh observance of the Indian holiday Vaisakhi, all of which occurred within several weeks of each other in April, involve suspense and suffering and death. Each of these holidays involves refusal. A refusal of toxic positivity or a comfortable take on life. But even more so, they are refusals of control, of death, and of the powers which lord over others with violence.

Easter: Refusing Death

Death, where is thy sting? This is one of the famous aphorisms which the apostle Paul cites in his interpretation of Jesus’s death. He was one who knew both the Roman persecution which killed Jesus (and would eventually kill him) and pain in his body which seemed to be more a matter of fate than injustice. Both of these frames shaped ancient and modern understandings of death and hope in the resurrection of Christ.

Death comes for us all. Even with modern medicine and advanced understandings of health, we still live at the whim of mortality. Few can go very long without at least a whiff, while many of us have faced death multiple times over, among our family and friends or even inside our own bodies. For Christians, God’s refusal of death in Christ is an existential comfort. Death does not win and it is not the end.

Some death, though, is quite obviously not arbitrary but violent, sometimes the work of reckless individuals, but at large scales, always the working of empires and powers and rulers, through malice or neglect and often both. To refuse death is not just to refuse the existential terror which can paralyze us or cause us to lash out, but also to refuse the powers who enact death. The Roman Empire crucified Jesus and some of his neighbors collaborated or remained silent. To refuse silence, to refuse collaboration, is to refuse death. This is an Easter imperative for Christians.

In poignant timing, Pope Francis, born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, died on Easter Monday after a long stretch of illness, which the Holy Father described as “suffering”. But death could not have him on Easter, when he made an appearance before crowds. Just days before, he and his staff faced off with U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance, where they had, “an exchange of opinions on the international situation, especially regarding countries affected by war, political tensions and difficult humanitarian situations, with particular attention to migrants, refugees, and prisoners."

To his dying day, Pope Francis refused to back away from death. To refuse death, one must not run away from it. One must face it. News emerged after his death that he had called a church parish in Gaza, Palestine, to offer comfort and support nearly every day since Israel’s bombardment began in October 2023. Not one to simply provide pastoral care, he consistently called for a ceasefire and an end to the war. He was unafraid to criticize Israel, rare among world leaders, though as a true peacemaker, he called on all warring parties to ceasefire, and consistently called for the return of Israeli hostages with more credibility than Israel’s own leaders.

Francis's final Easter message rings with these refusals of death, springing with Easter hope. To refuse death is not to fear it or run from it but rather to embrace life: “Christ is risen! These words capture the whole meaning of our existence, for we were not made for death but for life. Easter is the celebration of life! God created us for life and wants the human family to rise again!”

On his gravestone, the Pope requested a simple engraving: Francis. May Francis, who refused the power of death and loved with the life he had, rest in peace.

Passover: Refusing Pharaohs

My family had the honor of being invited to join a Seder meal with a group of Jewish young adults on the first day of Passover, April 12, led by two of my former university students. Though they are not yet Rabbis, both have scholarly mien and led us through a robust version of the ritual. My wife, who is Jewish, took joy in remembering the recitations and songs. We delighted in sharing this observance with our son Benji, his first Passover. Our teenagers and I relished crossing into this different religious tradition than our own with family and friends. And the food was great!

We read from the widely popular Maxwell House Haggadah. The Haggadah is an ancient Jewish text, probably around 1700 or 1800 years old, which sets the order of the Passover Seder and fulfills the obligation to recount the Exodus story to children on the first night of the festival. Maxwell House first published their English-Hebrew full text version in 1932 as a marketing campaign for coffee. This Seder added an orange to the plate, a symbol for gender and LGBTQ inclusion. One story about this goes that a Rabbi said, “A woman belongs on the bimah (altar) like an orange belongs on a Seder plate.” Prophecy fulfilled!

There are many other modified Haggadahs, some adjusted to particular concerns such as social justice. The “Global Justice Haggadah” from the American Jewish World Service starts by saying:

Our journey tonight, too, begins with an awakening: May this first cup of wine rouse each of us to respond to injustice—opening our eyes to the deep inequality that plagues our world today. May we recognize our individual and collective responsibility to pursue justice, believe in our capacity to make a difference, and recommit ourselves to building a better world for the future.

What all of these Haggadah share is a refusal of Pharaohs, the unjust powers who would subjugate and enslave and slaughter those under their power. For anti-Zionist Jews in Jewish Voice for Peace, their Passover liturgy specifically names the Pharaohs and explicitly refuses them:

This year the world feels unfathomably narrow. As we gather for Passover, the Israeli government furthers its genocidal project, destroying life and land all across Palestine. As we gather for Passover, modern day Pharaohs are rising to power all over the world.

In the United States, a fascist government is using the guise of fighting antisemitism to punish those who speak out for Palestinian freedom. This Passover gathering is an act of refusal. We will not allow our tradition, history, and identity, to be fuel for authoritarian crackdown.

As we left the wonderful Seder our friends hosted, my teenage son raised hackles about the theology of the plagues and especially the last one, the killing of the firstborn sons. I appreciated his point; it sounded like he was refusing a god who acted too much like Pharaoh, whose way was too much like Herod killing firstborn sons in his attempt to kill the young Jesus. My son did not like to see people punished for what their rulers did. What he wanted to see was not just a refusal of the Pharaohs but of their methods. He wanted to see people in solidarity with each other in their refusal of the powers. I was immensely proud of him for this liberating vision. None of us is free until all of us are free.

Vaisakhi: Refusing Self-centeredness

Now for a final refusal, in a festival a bit more traditionally spring-like in its warmth: Vaisakhi. Like many Indian holidays, this one is shared across different religions of the subcontinent. In Sikhism, the great social justice tradition, there is a story associated with this spring harvest holiday which demonstrates the selfless heart of their tradition.

Sikhs are known for being willing to put others first. In this story, which marks the first initiation of Saint-Soldiers in Sikhism, the tenth Guru, Gobind Singh Sahib, invited any who would give up their life for their faith to come forward. He took each of five volunteers inside a tent and came back out with a bloodied sword. In the end, it was revealed none had been killed, but all were honored as those selfless enough to become initiated as examples of the Sikh faith, who serve only the goodness of God and refuse to bow to any other power, whether the self or a ruler.

Perhaps the hope we hold is that, though we are willing to give our lives in the service of others, though we refuse to be self-centered, even so, we hope we can live and triumph and find justice and peace together in this world. May it be so, as we refuse the power of pharaohs and death over our lives.

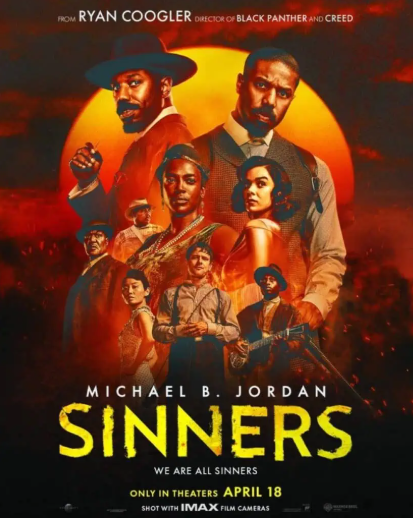

At the Movies: Sinners

The first summer blockbuster may have come early in the form of Sinners, the latest movie from acclaimed filmmaker Ryan Coogler, known for bringing Black Panther to the Marvel cinematic universe. His consistent partner has been actor Michael B. Jordan, who doubles in Sinners as the twins Smoke and Stack. And they have cooked up a hit in this Jim Crow era, deep south, blues musical, vampire flick. Read that sentence again if you need. This film may not be for you if you don’t go in for vampires or horror, but aside from that, it is a sonic masterpiece, full of stunning, wailing, enchanting music. If this does strike your fancy, it is worth seeing in a theater with a rowdy crowd. If it does not, check out the soundtrack!

As the title suggests, Sinners sings with religious imagery, though organized religion stays edges of the film. The lead character is a cousin to Smoke and Stack who is known as “Preacher Boy” Sammy because his father is the pastor of a local church. Crucial scenes rest on whether Sammy will respond to his father’s religiosity or follow his passion for music, a road which leads him among “sinners”. The devil is invoked early on, an early omen of the evil to come in the form of vampires. Elsewhere, Smoke visits Annie, who employs West African indigenous practices, in the Yoruba lineage, offering protection through talismans and invoking “Ashe”, or supernatural power. Even the vampires join in the fervor, reciting the Lord’s Prayer. The big picture of religion in Sinners presents a deeply supernatural but also chaotic and uncertain cosmos. Do rituals work or only money? Does music collapse the distance between the natural and supernatural, and would that necessarily be a good thing? Sinners sings a beautiful but complicated song on religion and don’t expect answers!

Paid subscribers can visit this newsletter on the website to add comments! I am always interested to hear what you think and discuss further.

For any feedback, reach out to me by email at: faithindiversityproject@gmail.com

Thank you for subscribing and see you next time! ~ Matt